In today's eco-conscious world, many consumers are eager to make environmentally-friendly choices. As a result, companies have recognized the value of appearing green and eco-friendly in order to attract these ethically-minded customers. However, not all companies are as green as they claim to be. This practice of misleading consumers through false environmental claims is known as greenwashing. Understanding greenwashing and its consequences is crucial for consumers to make informed choices and hold companies accountable for their actions.

Understanding Greenwashing

Definition and Brief History of Greenwashing

Greenwashing refers to the act of conveying a false impression or providing misleading information about a company's environmental practices or the environmental benefits of its products. This marketing strategy gained prominence in the late 1980s when environmental awareness started to grow. With the rise of sustainability as a popular concept, companies soon realized the potential for profit by positioning themselves as environmentally conscious, even if their true practices suggested otherwise.

One of the earliest instances of greenwashing can be traced back to the 1960s when oil companies started promoting their products as environmentally friendly despite their role in contributing to pollution and climate change. This marked the beginning of a trend where companies used deceptive tactics to appeal to the growing environmental concerns of consumers.

The Rise of Greenwashing in Modern Business

In recent years, greenwashing has become more prevalent due to the increased demand for sustainable products and practices. With the rise of social media and online platforms, companies have ample opportunities to showcase their green initiatives and connect with environmentally-conscious consumers. However, this has also led to a surge in false claims and misrepresentation, making it challenging for consumers to distinguish between genuinely eco-friendly companies and those using greenwashing strategies.

As consumers become more environmentally conscious and seek out sustainable options, companies are under pressure to appear green without necessarily making substantial changes to their operations. This has resulted in a proliferation of vague and unsubstantiated eco-friendly labels and marketing campaigns that aim to capitalize on the green trend without making meaningful contributions to sustainability.

The Techniques of Greenwashing

Vague Language and Misleading Labels

One of the most common techniques employed in greenwashing is the use of vague language and misleading labels. Companies may use buzzwords and phrases that imply environmental benefits without providing concrete evidence or data to support their claims. For example, a product labeled as "all-natural" may give the impression of being eco-friendly, but the use of such terms is unregulated and may not guarantee any ecological advantage.

Moreover, some companies strategically use color schemes and imagery on their packaging to evoke feelings of nature and sustainability, even if the product itself has little to no environmental benefit. This tactic aims to mislead consumers into believing they are making a green choice when, in reality, the product may have a significant carbon footprint or other negative impacts on the environment.

Irrelevant Claims and Hidden Trade-offs

Another method of greenwashing involves making irrelevant claims or hiding trade-offs. Companies may highlight a single eco-friendly aspect of their product or service while conveniently neglecting other harmful aspects. For instance, a company manufacturing electric vehicles may promote the zero-emission nature of their cars but fail to mention the environmental impact resulting from the extraction of the materials used in their production.

In addition, some companies engage in what is known as "hidden trade-offs," where they focus on one environmental issue, such as energy efficiency, while ignoring other significant sustainability concerns like water usage or waste generation. This selective presentation of information can create a skewed perception of a product's overall environmental impact, leading consumers to make choices based on incomplete or misleading data.

The Impact of Greenwashing

Consumer Deception and Trust Erosion

Greenwashing not only deceives consumers but also erodes their trust. When consumers believe they are making environmentally responsible choices but later discover they were misled, it can lead to feelings of frustration, skepticism, and disillusionment. Consequently, this undermines the efforts of genuinely eco-friendly companies and hampers the progress towards a sustainable future.

Moreover, the effects of greenwashing extend beyond individual consumer choices. When trust in environmental claims is eroded on a large scale, it can lead to a general sense of apathy and cynicism towards sustainability efforts. This can create a barrier to meaningful change at a societal level, as people become wary of supporting any environmental initiatives, unsure of their authenticity.

Environmental Consequences of False Claims

Greenwashing not only impacts consumers but also has severe environmental consequences. When companies exaggerate or fabricate their environmental commitments, it diverts attention and resources from genuinely sustainable initiatives. It also prevents consumers from supporting truly eco-friendly products and services, leading to a missed opportunity for positive environmental impact.

Furthermore, the proliferation of greenwashing can result in a dilution of the term "green" or "eco-friendly," making it harder for consumers to distinguish between authentic sustainability efforts and mere marketing ploys. This confusion can lead to a slowdown in the adoption of truly impactful environmental practices, as consumers become disillusioned and unsure of which companies to trust.

Legal Aspects of Greenwashing

Existing Laws and Regulations

Environmental claims made by companies may be subject to various laws and regulations. Many countries have guidelines in place to mitigate greenwashing and protect consumers from false advertising. For instance, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the United States provides guidelines on environmental marketing claims, ensuring they are truthful and backed by reliable scientific evidence.

Moreover, the European Union has implemented the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, which prohibits misleading environmental claims and ensures that businesses provide accurate information to consumers. This directive aims to promote fair competition and protect the interests of both consumers and the environment.

Legal Consequences for Companies

Companies found guilty of greenwashing face legal consequences. They may be subjected to fines, lawsuits, and damage to their reputation. Regulatory bodies are increasingly scrutinizing environmental claims made by companies and taking action against those who mislead consumers. This serves as a deterrent and encourages companies to engage in more authentic environmental practices.

In addition to financial penalties, companies involved in greenwashing may also experience a loss of consumer trust and loyalty. In today's age of social media and instant information sharing, negative publicity surrounding deceptive environmental claims can spread rapidly, damaging a company's brand image. This can have long-term implications on customer perception and market competitiveness, highlighting the importance of transparent and honest environmental marketing practices.

How to Spot Greenwashing

Tips for Identifying Misleading Claims

While greenwashing can be deceptive, there are ways for consumers to identify misleading claims and make informed decisions. Firstly, consumers should look for specific, verifiable information rather than relying solely on vague or generic statements. Secondly, scrutinizing certifications and environmental logos can provide insights into a company's true commitment to sustainability. Additionally, researching a company's track record or environmental initiatives can help uncover any inconsistencies or discrepancies.

Moreover, it is essential for consumers to delve deeper into a company's supply chain and production processes to assess the overall impact on the environment. Understanding how raw materials are sourced, manufacturing practices, and waste management strategies can reveal the true sustainability efforts of a brand. By considering the entire lifecycle of a product, consumers can make more informed choices that align with their values and environmental goals.

Resources for Consumer Awareness

Fortunately, several resources are available to aid consumer awareness and tackle greenwashing. Non-profit organizations such as the Greenwashing Index and the Global Ecolabelling Network provide valuable tools and information to help consumers navigate through green claims. By empowering themselves with knowledge, consumers can make more informed choices and promote genuine environmental progress.

Conclusion

Greenwashing is a pervasive issue that compromises consumer trust and hinders environmental progress. Understanding the techniques used by companies to mislead consumers and the consequences of greenwashing is vital in making informed choices. By staying vigilant and educating themselves about the true environmental impact of products and services, consumers can contribute to a more sustainable future and encourage companies to adopt genuinely eco-friendly practices.

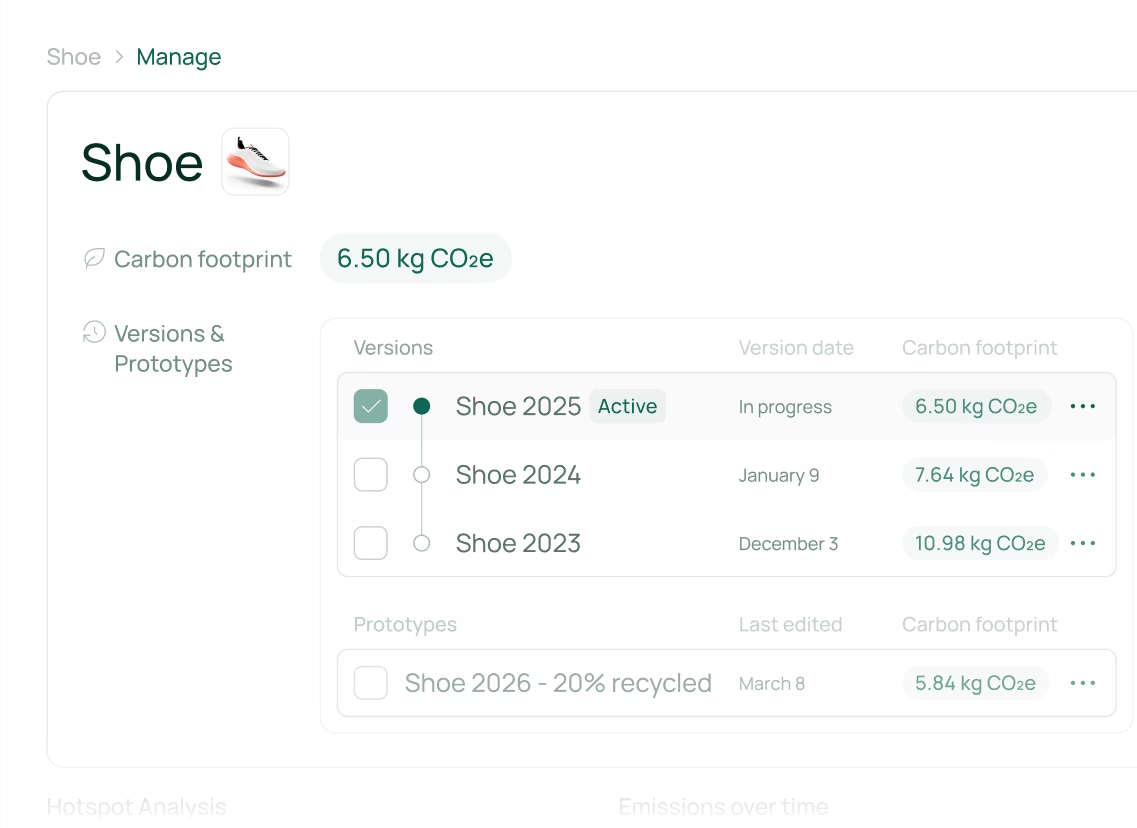

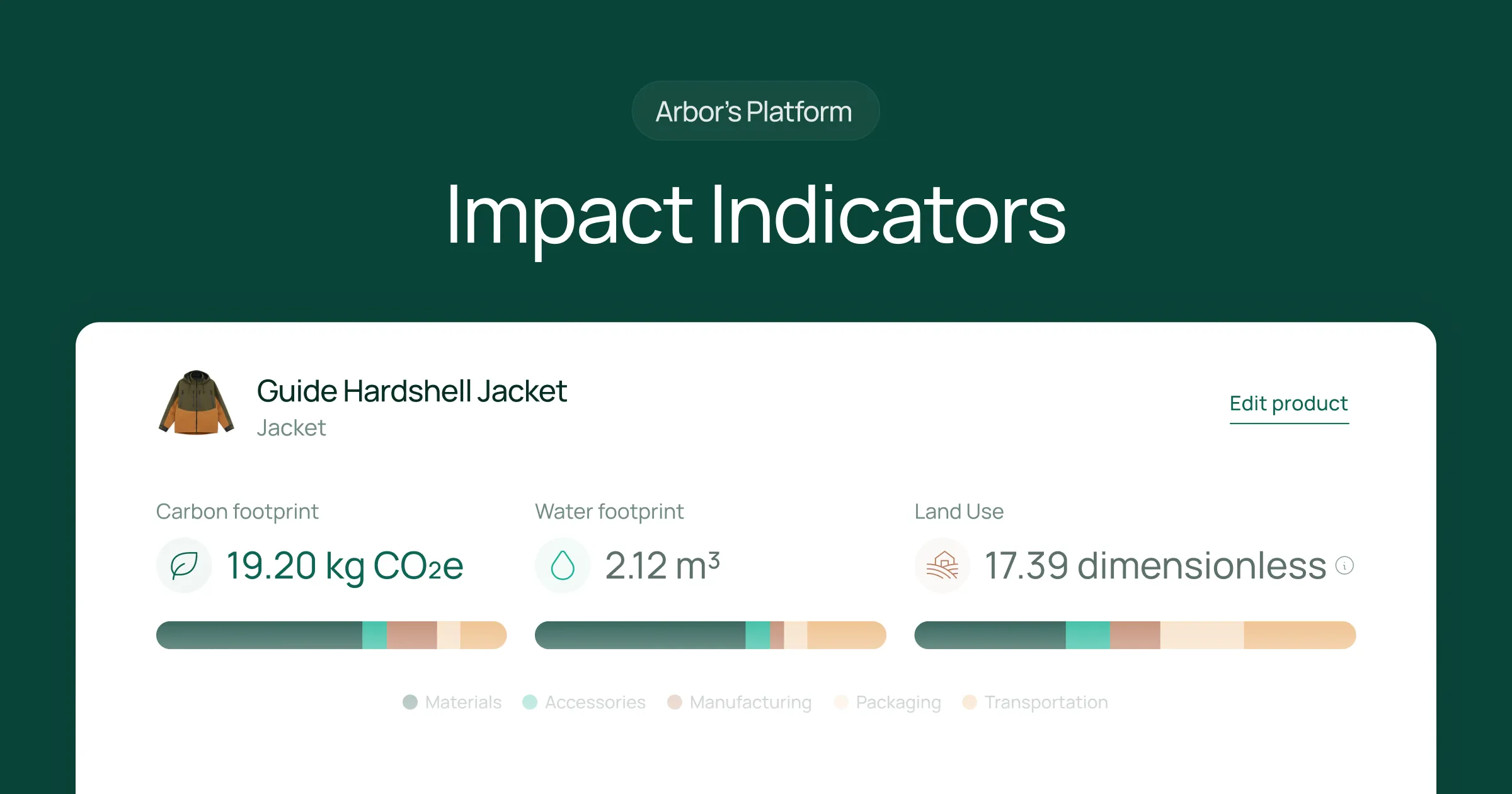

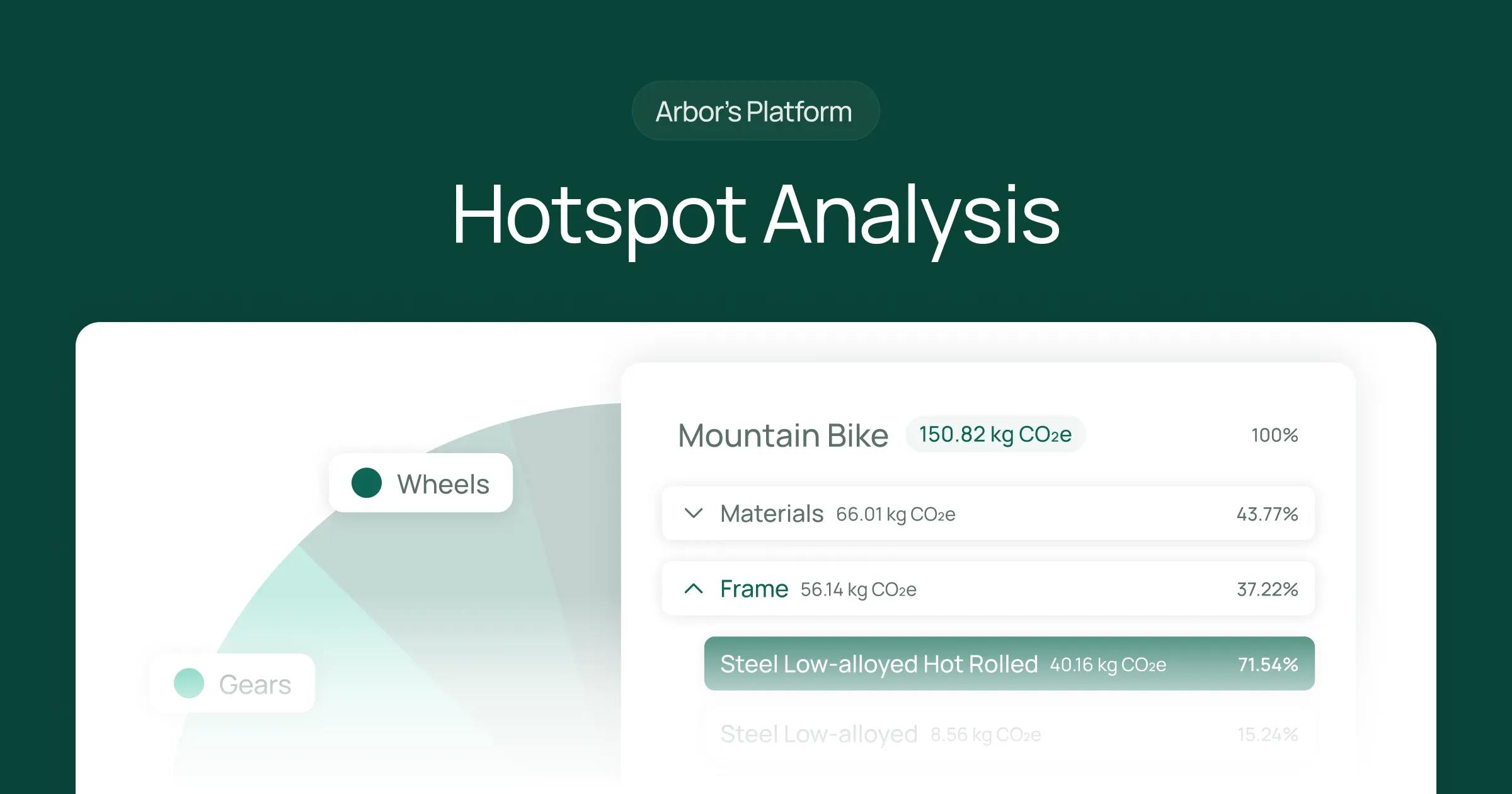

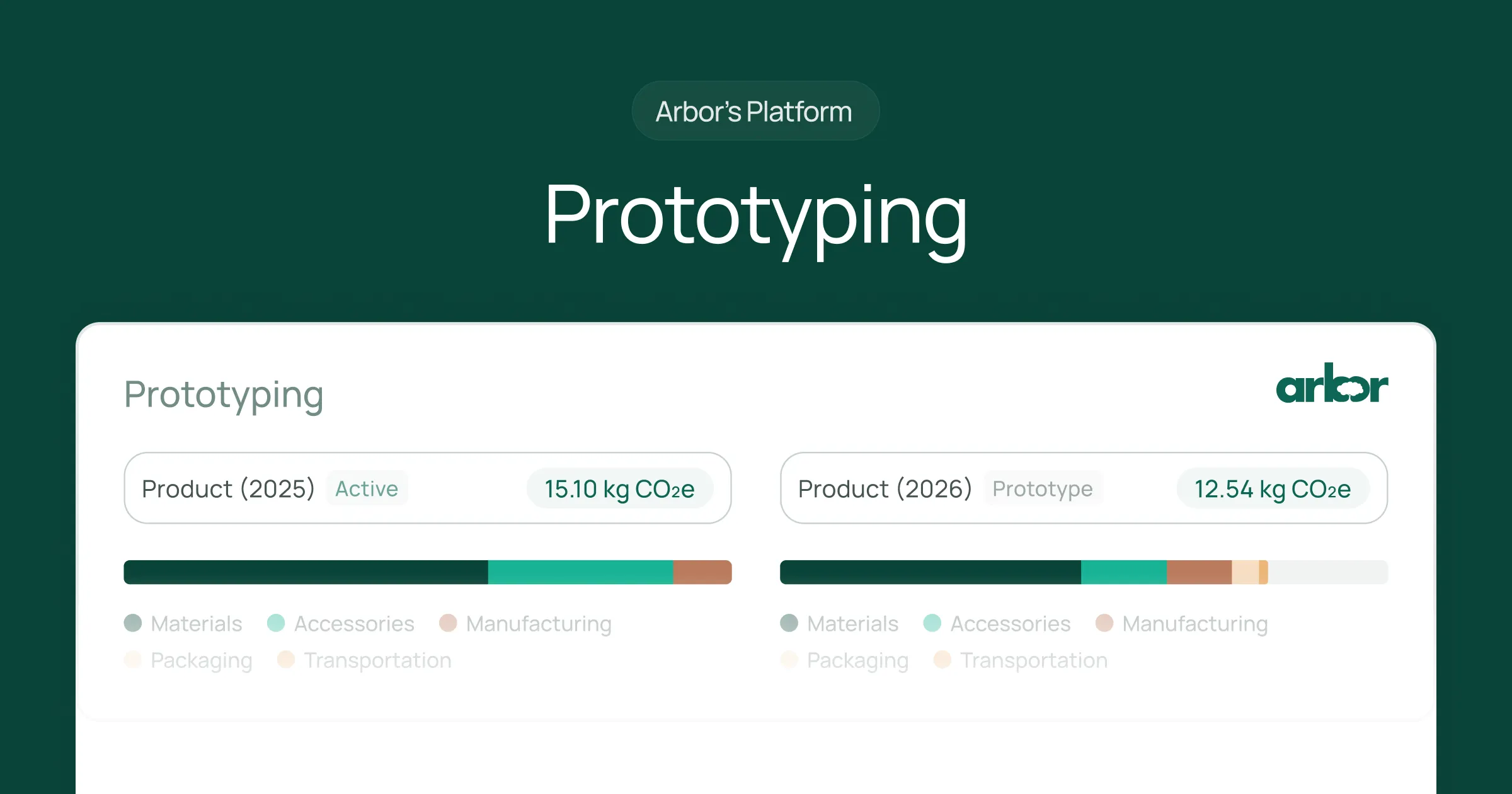

If you're an executive or project leader committed to steering your company towards genuine sustainability, Arbor is your ally in navigating the complexities of carbon management. With our industry-leading accuracy and easy-to-use platform, Arbor empowers you to calculate emissions, make informed environmental decisions, and ensure compliance with climate legislation. Don't let greenwashing undermine your efforts. Take control with our Carbon Calculator, Carbon Reporting, Carbon Insights, and Carbon Transparency tools. Embrace the clarity and confidence that comes with Arbor's material-level calculations, GRI-certified reporting, and region-specific data.

Request a demo today and take the first step towards transparent and effective carbon management.

Measure your carbon emissions with Arbor

Simple, easy carbon accounting.

.webp)

%20Directive.webp)

.webp)

%20Arbor.avif)

%20Arbor.avif)

.avif)

%20Arbor%20Canada.avif)

.avif)

%20Arbor.avif)

.avif)

_.avif)

.avif)

%20Arbor.avif)

%20Software%20and%20Tools.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20EU%20Regulation.avif)

.avif)

%20Arbor.avif)

_%20_%20Carbon%20101.avif)

.avif)